On Leaping over the Moon

by Thomas Traherne (1637-1674)

I saw new Worlds beneath the Water lie,

New People; yea, another Sky

And sun, which seen by Day

Might things more clear display.

Just such another

Of late my Brother

Did in his Travel see, and saw by Night,

A much more strange and wondrous Sight:

Nor could the World exhibit such another,

So great a Sight, but in a Brother.

Adventure strange! No such in Story we,

New or old, true or feigned, see.

On Earth he seem’d to move

Yet Heaven went above;

Up in the Skies

His body flies

In open, visible, yet Magic, sort:

As he along the Way did sport,

Over the Flood he takes his nimble Course

Without the help of feigned Horse.

As he went tripping o’er the King’s high-way,

A little pearly river lay

O’er which, without a wing

Or Oar, he dar’d to swim,

Swim through the air

On body fair;

He would not use or trust Icarian wings

Lest they should prove deceitful things;

For had he fall’n, it had been wondrous high,

Not from, but from above, the sky:

He might have dropt through that thin element

Into a fathomless descent;

Unto the nether sky

That did beneath him lie,

And there might tell

What wonders dwell

On eath above. Yet doth he briskly run,

And bold the danger overcome;

Who, as he leapt, with joy related soon

How happy he o’er-leapt the Moon.

What wondrous things upon the Earth are done

Beneath, and yet above the sun?

Deeds all appear again

In higher spheres; remain

In clouds as yet:

But there they get

Another light, and in another way

Themselves to us above display.

The skies themselves this earthly globe surround;

W’are even here within them found.

On heav’nly ground within the skies we walk,

And in this middle centre talk:

Did we but wisely move,

On earth in heav’n above,

Then soon should we

Exalted be

Above the sky: from whence whoever falls,

Through the long dismal precipice,

Sinks to the deep abyss where Satan crawls

Where horrid Death and Despair lies.

As much as others thought themselves to lie

Beneath the moon, so much more high

Himself and thought to fly

Above the skarry sky,

As that he spied

Below the tide.

Thus did he yield me in the shady night

A wonsdrous and instructive light,

Which taught me that under our feet there is

As o’er our heads, a place of bliss.

To the same purpose; he, not long before

Brought home from nurse, going to the door

To do some little thing

He must not do within,

With wonder cries,

As in the skies

He saw the moon, "O yonder is the moon

Newly come after me to town,

That shin’d at Lugwardin but yesternight,

Where I enjoy’d the self-same light."

As if it had ev’n twenty thousand faces,

It shined at once in many places;

To all the earth so wide

God doth the stars divide

With so much art

The moon impart,

They serve us all; serve wholly ev’ry one

As if they served him alone.

While every single person hath such store,

’Tis want of sense that makes us poor.

This is a poem that at first reading seems to contain strange, dream-like floating forms, like a Chagall painting. But eventually we discover its strict inner logic.

The poet has a brother, who is walking along at night — tripping o’er the King’s highway, and comes to a brook (in stanza 3). He leaps across it. As he does so he sees the reflection of the moon in the water of the brook. So, as the title promises, he leaps over the moon. If he had fallen into the brook (stanza 4), he would have fallen right down to the moon of the reflection. This would be a fathomless descent through the thin element of the water. Eventually he would arrive in another world, the reflected sky, and he could then have told the creatures he met there what it was like on earth above.

From the third stanza we work our way back to the beginning of the poem, and find that the story has been told backwards. We then see that the poet has had a sun-experience, corresponding to the moon-experience of the brother. Stanzas five and six continue the poet’s reflections on his sun-experience, while stanza seven returns us to the brother again, continuing the story of stanza four, while the last two stanzas tell a story of another encounter of the brother with the moon, connected to the first but interpeted differently.

But this is just the skeleton. As we explore the body of the poem further, we find ourselves in a maze of Christian and pagan references, astronomical ideas, echoes of the Bible and Milton. We create theories about the relation between poet and brother, and their relation to the poem itself. We see the Lord’s Prayer (on earth as it is in heaven), Jesus’s teaching of God’s bounty to man, the idea of the plurality of worlds, for which Bruno had payed with his life seventy years before, and which was to be urged on the world in the popular scientific writings of Derham seventy years later, and mysticism, with big being seen in little and little in big, like Julian of Norwich’s hazelnut. The poem is vast.

Stanza three: Tripping suggests making a journey, skipping, and also stumbling, and prepares us well for the many types of motion which are mentioned in the rest of the poem. And the King’s highway suggests the social and civic world, which the brother is about to leave behind, as well as reminding us perhaps of the Restoration of 1660. The pun of pearly river (pearl and purl), takes us into the word play of o’er / or / oar, at the same time confusing us with the idea that wings for flying, or oars for rowing, are equally valid aids to transport for a seventeenth century gentleman needing to get across a brook. Then, neither flying nor rowing, he adopts swimming, not swimming in water but swimming in the air. Either he, like an angel, is the body fair supported on the air, or more plausibly, the air is the body fair which supports him as he flies. At this point the poem is allowed to take off with a certain hyperbolic grandeur,

He would not use or trust Icarian wingswhich matches the take-off of the brother, as he lifts himself into the air. There is a certain comedy here, the comedy of overstatement. The Icarian wings, destroyed by the sun, take us back momentarily to the sun-experience of the poet, as well as reminding us that not everything bearing wings that falls has to be angelic. But inevitably the fall from above the sky makes us think of a falling angel.

Lest they should prove deceitful things

Had Traherne read Milton? Paradise Lost appeared in 1667. Traherne died in 1774. If he had, does this poem post-date his reading? Whatever the answer, we see the Miltonic cosmogony here. He is above the sky, in the Empyrean, and his fall might take him to a place,

As far remov’d from God and light of Heav’nIn this poem and Paradise Lost, the fall is down a precipice. The brother,

As from the Center thrice to th’ utmost Pole.

Through the long dismal precipice,While Satan says to Beelzebub in Book I,

Sinks to the deep abyss where Satan crawls

... The Sulphurous Hail

Shot after us in storm, oreblown hath laid

The fiery Surge, that from the Precipice Of Heav’n receiv’d us falling ...

This poem makes us think about truth in lyric poetry. We accept a novel as being untrue, although drawing from the author’s experience. An autobiography by contrast is meant to be true, and if it is not, the author can be accused of deception. A lyric poem may record a true event, but it does not have to, and we don’t insist that Keats saw a bright star before writing the Bright Star sonnet. This is especially true of metaphysical poetry, like this one, where the poem is so often created from the most minute of events. Marvell’s drop of dew, for example. We would think less about what really happened in Traherne’s poem if it had been the poet who had the experience, rather than the poet’s brother.

A friend or a lover may easily be invented, but inventing a brother is more difficult. We can trace brothers through family history. As it is, we know that Thomas did have a brother, Philip, a priest like Thomas himself, and finally Thomas literary executor, where he did a very bad job, according to later scholars, of editing Thomas unpublished writings, this poem among them. Did Philip have this mystical experience and relate it to his brother, or did Thomas invent the experience from a mundane tale of Philip’s? How do poet and brother in the poem relate to the poet and brother of real life?

Philip in the poem is almost a twin of the poet’s: one cannot imagine his lunacy being more extreme than that of the brother who describes him. But he is like a negative twin. He is to the moon as the poet is to the sun, and to the night as the poet is to the day. He is the Enkidu to Thomas’s Gilgamesh. But despite this symbolic connection, he is fully real. The mention of convalescence (brought home from nurse), and using an outside toilet,

going to the door(it can be nothing else), at Lugwardin, in which strangely named village the brothers Traherne did indeed live, impresses us with its truth.

To do some little thing

He must not do within,

The poem centres upon a reflection, a standard metaphysical device. As in Marvell’s drop of dew (already mentioned),

The clear region where twas bornwhere the dewdrop reflects back the air that gave birth to it, so that inside the dewdrop you see the world that is outside it.

Round in itself encloses

And in its little globe’s extent

Frames as it can its native element.

Again in Donne,

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appeares,where the poet sees his reflection in his lover’s eye, and she sees hers in his. And again in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 24, where the poet sees the sun reflected in his lover’s eyes.

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest,

Where can we find two better hemispheres

Without sharp North, without declining West?

But the detail that separates out Traherne’s poem is that the reflection is

nowhere explicitly mentioned, and we have to work out for ourselves that

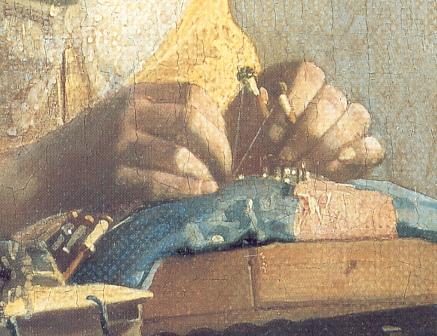

that is what the poem is all about. It is like Vermeer’s picture, the

Lacemaker, which became an obsession to Dali. What caused the later artist such

fascination, apparently, is that the whole image centres around one detail,

the sharp point of a needle, on which the plump woman is concentrating.

You know it is there, although it is not in the picture.